|

CAMP X FORCED LANDINGS AND A CAMP X CONNECTION

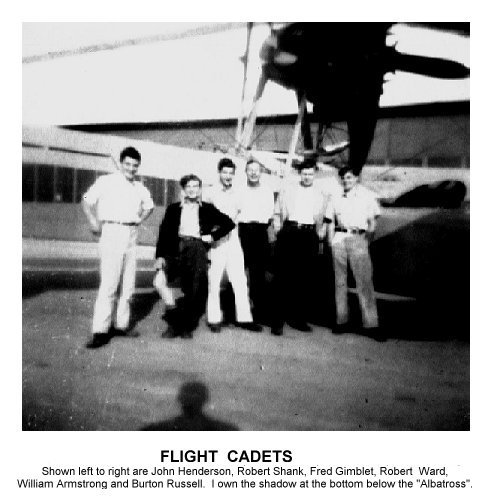

As far as I know, only one of the seven air cadets in the flying course of 1948 at the Ontario County Flying Club was ever involved in a real forced landing, and this occurred during the winter after I left Oshawa to work at the Connaught Labs University Division at Queen's Park and College Street in Toronto. The story was relayed by another cadet, Burt Russell, so I trust its accuracy.

It seems that Bob Ward flew out to the family farm near Markham one frosty day in January of 1949. He wanted to catch the attention of those on the ground, and did what most of us were accustomed to doing. He gunned the throttle. [I've done this a few times - once before doing a tailspin over the chimney of our home on Alexander Boulevard; we lived west of the Park Road boundary with Oshawa.] However, when he pulled the throttle knob back, the engine stopped and the propeller stood like a stiff soldier in front of his field of vision. He had forgotten the need for turning on the cabin heat to prevent the gas line from freezing up. Being over farmland, he had little trouble locating a possible place to land. Unfortunately, Bob misjudged his approach and lost the undercarriage while negotiating a fence. The wings were also damaged when the plane went between two trees. Other-wise, it was a safe landing, and "Schnook" walked home. I gave him this nickname in the summer of 1948 after he tried to spin the propeller of an "aircoup" and it clouted him; the aircraft has an automatic starter and objected to this mistreatment. That event occurred during the period of our ground school on weather, and I felt that the term "Chinook" seemed to fit. It was not long thereafter that the slang term was heard beyond our group of seven cadets at the flying club. I overheard someone at the Oshawa Collegiate and Vocational Institute being called a SCHNOOK, and there was some debate over its origin. "Perhaps it's an acronym, like SNAFU (Situation Normal; All Fouled UP)?" one person ventured. Nice Try. Nor could the origin be attributed to that radio character "Baby Snooks". [I recall the comedy movie of 1960, Wake Me When It's Over, directed by Mervin LeRoy, and starring Dick Shawn, Jack Warden, Don Knotts, Ernie Kovacs, Margo Moore and others. I was jolted when I heard the term "schnook" during the opening scenes. The word had certainly travelled quickly!]

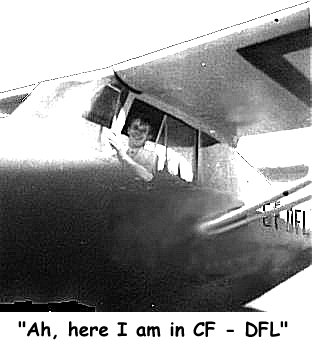

It seems that Bob Ward flew out to the family farm near Markham one frosty day in January of 1949. He wanted to catch the attention of those on the ground, and did what most of us were accustomed to doing. He gunned the throttle. [I've done this a few times - once before doing a tailspin over the chimney of our home on Alexander Boulevard; we lived west of the Park Road boundary with Oshawa.] However, when he pulled the throttle knob back, the engine stopped and the propeller stood like a stiff soldier in front of his field of vision. He had forgotten the need for turning on the cabin heat to prevent the gas line from freezing up. Being over farmland, he had little trouble locating a possible place to land. Unfortunately, Bob misjudged his approach and lost the undercarriage while negotiating a fence. The wings were also damaged when the plane went between two trees. Other-wise, it was a safe landing, and "Schnook" walked home. I gave him this nickname in the summer of 1948 after he tried to spin the propeller of an "aircoup" and it clouted him; the aircraft has an automatic starter and objected to this mistreatment. That event occurred during the period of our ground school on weather, and I felt that the term "Chinook" seemed to fit. It was not long thereafter that the slang term was heard beyond our group of seven cadets at the flying club. I overheard someone at the Oshawa Collegiate and Vocational Institute being called a SCHNOOK, and there was some debate over its origin. "Perhaps it's an acronym, like SNAFU (Situation Normal; All Fouled UP)?" one person ventured. Nice Try. Nor could the origin be attributed to that radio character "Baby Snooks". [I recall the comedy movie of 1960, Wake Me When It's Over, directed by Mervin LeRoy, and starring Dick Shawn, Jack Warden, Don Knotts, Ernie Kovacs, Margo Moore and others. I was jolted when I heard the term "schnook" during the opening scenes. The word had certainly travelled quickly!]  Our training in "forced landings" was not extensive. Milt McDougall, my instructor, sat in the back seat of the Aeronca with the markings DNL on August 22, 1948, after several practices at spot landings on the previous day, and asked me to head south. The site for the forced landings was south of the airport at the boundary between East Whitby and Whitby Townships and close to the shore of Lake Ontario, where there were quite a few flat, level pastures. It was an enjoyable experience to throttle back, listen to the quietness of the idling propeller as the plane comes in about fifteen feet above the ground and, just as it rushed up so that blades of grass came clearly into focus, advance the throttle to climb, engine roaring, through the updrafts at the shore. On one such occasion, I waived back at a startled farmer who was driving his wagon-load of hay through a pasture about two hundred feet to my right. Make-believe emergencies are definitely more fun than the real thing.

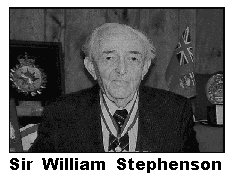

Our training in "forced landings" was not extensive. Milt McDougall, my instructor, sat in the back seat of the Aeronca with the markings DNL on August 22, 1948, after several practices at spot landings on the previous day, and asked me to head south. The site for the forced landings was south of the airport at the boundary between East Whitby and Whitby Townships and close to the shore of Lake Ontario, where there were quite a few flat, level pastures. It was an enjoyable experience to throttle back, listen to the quietness of the idling propeller as the plane comes in about fifteen feet above the ground and, just as it rushed up so that blades of grass came clearly into focus, advance the throttle to climb, engine roaring, through the updrafts at the shore. On one such occasion, I waived back at a startled farmer who was driving his wagon-load of hay through a pasture about two hundred feet to my right. Make-believe emergencies are definitely more fun than the real thing.  I was not aware of it at the time, but the fields where my "forced landings" took place were definitely off-limits just a couple of years earlier, and their true purpose was still a highly guarded secret. It had been, and still was, the site of Camp X until closed in 1951; it was the brainchild of Sir William Stephenson, a long-time friend of Sir Winston Churchill, who gave him the wartime code-name "Intrepid" when, according to General Sir Colin Cubbins (Chief of the Special Operations Executive), he was appointed the supreme authority in the SOE and of British Security Co-ordination in North and South America. It had been Sir William Stephenson who provided Churchill with intelligence reports concerning developments in Germany prior to World War II. As Intrepid, Stephenson established a headquarters in the "technically neutral" city of New York at The Rockefeller Center when the USA had absolutely no secret intelligence service; the sign on his office door read "Passport Control". If you read enough accounts of the life of this "quiet Canadian", you will conclude that Stephenson could be several places at one time. Born at Point Douglas near Winnipeg, Manitoba, he had been decorated during World War I with the Military Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Croix de Guerre avec Palmes and the Legion d'Honneur. Stephenson is credited with the invention of the wire photo and a method of sending pictures by radio.

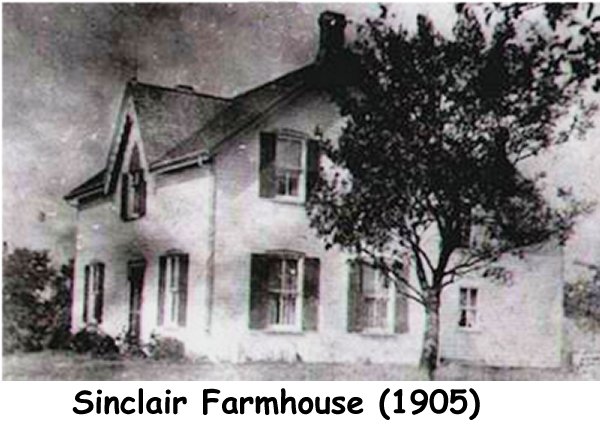

I was not aware of it at the time, but the fields where my "forced landings" took place were definitely off-limits just a couple of years earlier, and their true purpose was still a highly guarded secret. It had been, and still was, the site of Camp X until closed in 1951; it was the brainchild of Sir William Stephenson, a long-time friend of Sir Winston Churchill, who gave him the wartime code-name "Intrepid" when, according to General Sir Colin Cubbins (Chief of the Special Operations Executive), he was appointed the supreme authority in the SOE and of British Security Co-ordination in North and South America. It had been Sir William Stephenson who provided Churchill with intelligence reports concerning developments in Germany prior to World War II. As Intrepid, Stephenson established a headquarters in the "technically neutral" city of New York at The Rockefeller Center when the USA had absolutely no secret intelligence service; the sign on his office door read "Passport Control". If you read enough accounts of the life of this "quiet Canadian", you will conclude that Stephenson could be several places at one time. Born at Point Douglas near Winnipeg, Manitoba, he had been decorated during World War I with the Military Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Croix de Guerre avec Palmes and the Legion d'Honneur. Stephenson is credited with the invention of the wire photo and a method of sending pictures by radio.  University of Toronto alumnus Benjamin de Forest (Pat) Bayly contributed to the Allied effort by developing a cipher machine at Camp X. The surviving files of the S.O.E. (Special Operations Executive) are still classified, but details of special forces units and training are surfacing. Camp X became a highly top-secret, training base for spies and saboteurs before they were sent to Europe. Tall radio towers on the former Sinclair estate were explained away as C.B.C. communications facilities, if anyone had been curious enough to ask. It is believed that the base was established close enough to Lake Ontario so that U.S. trainees could be surrepticiously admitted to the "Top Secret" operation. Being directly south of the western boundary of the Oshawa airport had obvious advantages as well; the connecting gravel road through Thornton's Corners, on the outskirts of Oshawa in those days, was fairly isolated.

University of Toronto alumnus Benjamin de Forest (Pat) Bayly contributed to the Allied effort by developing a cipher machine at Camp X. The surviving files of the S.O.E. (Special Operations Executive) are still classified, but details of special forces units and training are surfacing. Camp X became a highly top-secret, training base for spies and saboteurs before they were sent to Europe. Tall radio towers on the former Sinclair estate were explained away as C.B.C. communications facilities, if anyone had been curious enough to ask. It is believed that the base was established close enough to Lake Ontario so that U.S. trainees could be surrepticiously admitted to the "Top Secret" operation. Being directly south of the western boundary of the Oshawa airport had obvious advantages as well; the connecting gravel road through Thornton's Corners, on the outskirts of Oshawa in those days, was fairly isolated.

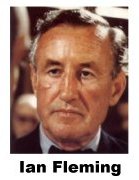

One of the trainees at Camp X was Ian Fleming, who failed his first test ... an order to "kill" an unarmed "enemy" using a gun loaded with blanks. The son of a Scottish banker, he became the right-hand man of spy-master Admiral John Godfrey in Naval Intelligence during World War II. He worked closely with William Stephenson at the North American Headquarters and training centres, before commanding his #30 AU (Assault Unit). Several years after the war, Ian created his famous James Bond character (agent 007) and many episodes were closer to the true exploits than fiction in many respects. William Stephenson may have been the model for "M". Paul Dehn, in charge of propaganda training at Camp X and author of Orders to Kill, co-wrote the screen version of Goldfinger based on the book by Fleming. In any case, the movies continued to be made with different lead actors into the 1980's and 1990's. Sean Connery, born in 1930, was the first.

One of the trainees at Camp X was Ian Fleming, who failed his first test ... an order to "kill" an unarmed "enemy" using a gun loaded with blanks. The son of a Scottish banker, he became the right-hand man of spy-master Admiral John Godfrey in Naval Intelligence during World War II. He worked closely with William Stephenson at the North American Headquarters and training centres, before commanding his #30 AU (Assault Unit). Several years after the war, Ian created his famous James Bond character (agent 007) and many episodes were closer to the true exploits than fiction in many respects. William Stephenson may have been the model for "M". Paul Dehn, in charge of propaganda training at Camp X and author of Orders to Kill, co-wrote the screen version of Goldfinger based on the book by Fleming. In any case, the movies continued to be made with different lead actors into the 1980's and 1990's. Sean Connery, born in 1930, was the first.  One of the last persons to make use of the camp, which became an army base in 1945, was the Soviet spy and defector Igor Gouzenko, who hid out from the public until the base closed in 1951 when East Whitby was annexed by Oshawa. Today, the site of Camp X is part of an industrial park with an L.C.B.O. warehouse to the north and a portion of the "Trans-Canada Walking Trail" to the south along the lakeshore.

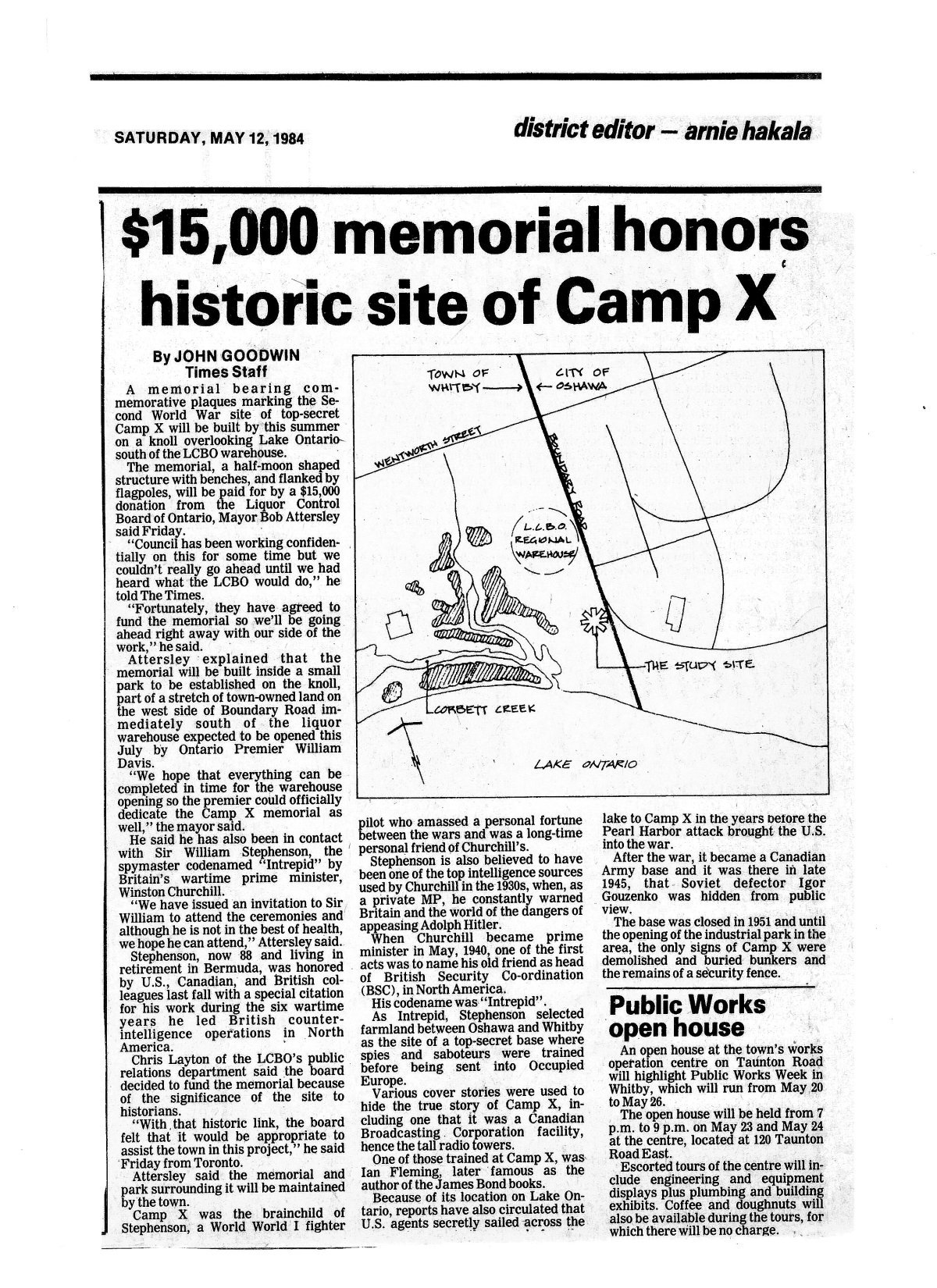

One of the last persons to make use of the camp, which became an army base in 1945, was the Soviet spy and defector Igor Gouzenko, who hid out from the public until the base closed in 1951 when East Whitby was annexed by Oshawa. Today, the site of Camp X is part of an industrial park with an L.C.B.O. warehouse to the north and a portion of the "Trans-Canada Walking Trail" to the south along the lakeshore.  MAP OF CAMP X

In the final year of the war, one of my hobbies included the building of "crystal sets". On this simple radio, with a copper feeler touching the galena crystal, I could fine-tune a home-made coil to receive the familiar call signal "Y-Z" from the Malton Airport (dah-dit-dah-dah dah-dah-dit-dit). On other occasions, by setting the aerial parallel to the lake, I received strong signals which could be best described as rapid Morse. Were they from Camp X, I wonder? The camp did train radio operators in encoding, decyphering, sending and receiving under the cover as a CBC facility. It was a base for training operatives and secret agents in self-defence, sabotage, house break-ins, target practice, spying, survival, stalking, code breaking, intellingence gathering, underwater demolition, foreign languages, disguises, underground resistance, parachuting (with drops inside a barn), use of RDX plastic explosives, and making forged documents, propaganda films and leaflets.

In the final year of the war, one of my hobbies included the building of "crystal sets". On this simple radio, with a copper feeler touching the galena crystal, I could fine-tune a home-made coil to receive the familiar call signal "Y-Z" from the Malton Airport (dah-dit-dah-dah dah-dah-dit-dit). On other occasions, by setting the aerial parallel to the lake, I received strong signals which could be best described as rapid Morse. Were they from Camp X, I wonder? The camp did train radio operators in encoding, decyphering, sending and receiving under the cover as a CBC facility. It was a base for training operatives and secret agents in self-defence, sabotage, house break-ins, target practice, spying, survival, stalking, code breaking, intellingence gathering, underwater demolition, foreign languages, disguises, underground resistance, parachuting (with drops inside a barn), use of RDX plastic explosives, and making forged documents, propaganda films and leaflets.  During my flight training after the war, as previously noted, I practised tailspins and make-believe forced landings at relatively easy locations around the farmlands of East Whitby including the lakeshore south of the Oshawa airport. I learned later that the Soviet defector Igor Gouzenko was being hidden nearby at Camp X during my training exercises. [See further data about Igor Gouzenko in the POSTSCRIPT at the end of this tale.] Before the flight course was completed, Milt MacDougal took me north of the airport near what we call the "ridge" which was the shoreline of an ancient lake, Lake Iroquois. Milt, like most flying instructors, had a quiet sense of humour. The terrain was rough, woods-covered country with ravines and a tributary of the creek which runs to the east of the airport. Most importantly, there was a broad power-line corridor, few roads and even fewer farm pastures. It was here that Milt chose to power back. Where would you land? As the plane descended in a careful arc under my control, I realized that there were scant possibilities. A narrow road with overhanging tree branches? The clearing beside the power lines? I indicated the latter choice, and Milt took over. I never did find out whether he approved of the selection. Of greater probability, is the fact that the law prohibits that choice.

During my flight training after the war, as previously noted, I practised tailspins and make-believe forced landings at relatively easy locations around the farmlands of East Whitby including the lakeshore south of the Oshawa airport. I learned later that the Soviet defector Igor Gouzenko was being hidden nearby at Camp X during my training exercises. [See further data about Igor Gouzenko in the POSTSCRIPT at the end of this tale.] Before the flight course was completed, Milt MacDougal took me north of the airport near what we call the "ridge" which was the shoreline of an ancient lake, Lake Iroquois. Milt, like most flying instructors, had a quiet sense of humour. The terrain was rough, woods-covered country with ravines and a tributary of the creek which runs to the east of the airport. Most importantly, there was a broad power-line corridor, few roads and even fewer farm pastures. It was here that Milt chose to power back. Where would you land? As the plane descended in a careful arc under my control, I realized that there were scant possibilities. A narrow road with overhanging tree branches? The clearing beside the power lines? I indicated the latter choice, and Milt took over. I never did find out whether he approved of the selection. Of greater probability, is the fact that the law prohibits that choice.A VISIT TO THE SITE OF CAMP X

The newspaper article. "$15,000 memorial honours historic site of Camp X", was dated Saturday, May 12, 1984. A memorial bearing commemorative plaques was to be built during the summer. I may have been too busy to attend at the time and, in any case, I never learned when the ceremony would take place, but the clipping was duly saved along with my intention to visit the site one day. What was my reason? The site appeared to be located near the boundary of Whitby and East Whitby at the lakeshore and immediately south of the Oshawa Airport. My first flying lessons on forced landings had occurred over that relatively flat terrain.

My initial (and belated) reconnaissance trip was on March 24, 1995. The day was sunny with a few fluffy alto cumulus clouds, just right for getting my bearings, checking out the modern industrial development, making note of general land features and noting the roads which would be included in my rough map. I like to document such observations for future reference. Driving to Oshawa on the 401 highway, I took the exit for Park Road, which does a slight jog, since "College Hill" prevents it from going straight south. From Bloor Street West, the Base Line Road (There's absolutely no rhyme nor reason for the name "Bloor" in this area!), I proceeded to the point where Park Road continues south to the lakeshore. Park Road marked the boundary between the township of East Whitby and the City of Oshawa during World War II; it was not until 1951 that Oshawa extended its western boundary to just west of Thornton Road, eliminating East Whitby and legitimately gaining the airport which already bore the name "Oshawa Airport", the entrance to which is at the end of the northern extension of Stevenson Road. During my search of the area south of the 401, I recalled the former farmlands and checked that Wentworth Street (of the City of Oshawa) had ended at the boundary. Returning to Bloor Street West, I drove over to Stevenson Road South. Today, Wentworth Street continues to the west of Stevenson Road, and the land on both sides of Stevenson Road is now occupied by the General Motors "South Plant". Aside from the fact that these had been gravel roads during the war, the north/south roads between Park Road and the Town Line still headed straight as an arrow to the lakeshore and they were connected to their extensions beyond Highway 2 (King Street West or the old "Kingston Road"). Since I had other business in Oshawa, no more time could be spent that day on my search.

My initial (and belated) reconnaissance trip was on March 24, 1995. The day was sunny with a few fluffy alto cumulus clouds, just right for getting my bearings, checking out the modern industrial development, making note of general land features and noting the roads which would be included in my rough map. I like to document such observations for future reference. Driving to Oshawa on the 401 highway, I took the exit for Park Road, which does a slight jog, since "College Hill" prevents it from going straight south. From Bloor Street West, the Base Line Road (There's absolutely no rhyme nor reason for the name "Bloor" in this area!), I proceeded to the point where Park Road continues south to the lakeshore. Park Road marked the boundary between the township of East Whitby and the City of Oshawa during World War II; it was not until 1951 that Oshawa extended its western boundary to just west of Thornton Road, eliminating East Whitby and legitimately gaining the airport which already bore the name "Oshawa Airport", the entrance to which is at the end of the northern extension of Stevenson Road. During my search of the area south of the 401, I recalled the former farmlands and checked that Wentworth Street (of the City of Oshawa) had ended at the boundary. Returning to Bloor Street West, I drove over to Stevenson Road South. Today, Wentworth Street continues to the west of Stevenson Road, and the land on both sides of Stevenson Road is now occupied by the General Motors "South Plant". Aside from the fact that these had been gravel roads during the war, the north/south roads between Park Road and the Town Line still headed straight as an arrow to the lakeshore and they were connected to their extensions beyond Highway 2 (King Street West or the old "Kingston Road"). Since I had other business in Oshawa, no more time could be spent that day on my search.  On Sunday, April 2, 1995, the clock had been set ahead for daylight saving time and, although it was approaching the noon hour, I felt as though it was still mid-morning. The sun was co-operating again as I took the Park Road exit. This time I drove westward along Bloor Street West to a sign which said Thornton Road South; I made the turn south, and got no further than a GO Parking Lot. It was impossible to proceed in a southerly direction from there. Why? Retracing the path back to Bloor Street West, I discovered that a fence blocked any further travel north along Thornton Road. When Highway 401 or the "Macdonald-Cartier Freeway" was planned and constructed during the early 1950's, access to the north had not been restricted on any other north-south road in East Whitby Township. Why? I returned to Stevenson Road South, proceeded down to Wentworth Street, drove west --- and located the continuation of Thornton Road South. A sign indicated that the road to the north would lead into a Canadian National Railway rail yard. For some years after the war, there were level crossings for the CNR trains at all of the roads in East Whitby. For Thornton Road South in particular, what an imaginative way to discourage unwanted guests at a secret base; all that would be required was to park a few railway cars across the road on a siding.

On Sunday, April 2, 1995, the clock had been set ahead for daylight saving time and, although it was approaching the noon hour, I felt as though it was still mid-morning. The sun was co-operating again as I took the Park Road exit. This time I drove westward along Bloor Street West to a sign which said Thornton Road South; I made the turn south, and got no further than a GO Parking Lot. It was impossible to proceed in a southerly direction from there. Why? Retracing the path back to Bloor Street West, I discovered that a fence blocked any further travel north along Thornton Road. When Highway 401 or the "Macdonald-Cartier Freeway" was planned and constructed during the early 1950's, access to the north had not been restricted on any other north-south road in East Whitby Township. Why? I returned to Stevenson Road South, proceeded down to Wentworth Street, drove west --- and located the continuation of Thornton Road South. A sign indicated that the road to the north would lead into a Canadian National Railway rail yard. For some years after the war, there were level crossings for the CNR trains at all of the roads in East Whitby. For Thornton Road South in particular, what an imaginative way to discourage unwanted guests at a secret base; all that would be required was to park a few railway cars across the road on a siding.  I turned south. Before long, Thornton Road South made a wide circular turn to the west. Why? Soon I would conclude that this curve led directly into the secret base known as Camp X. At the end of this curve, I drove a short distance along another curving road, Phillip Murray Avenue, and almost missed a sign which read "Intrepid Park - Town of Whitby". I could also see a curved wall and what appeared to be four metal standards or flag poles.

I turned south. Before long, Thornton Road South made a wide circular turn to the west. Why? Soon I would conclude that this curve led directly into the secret base known as Camp X. At the end of this curve, I drove a short distance along another curving road, Phillip Murray Avenue, and almost missed a sign which read "Intrepid Park - Town of Whitby". I could also see a curved wall and what appeared to be four metal standards or flag poles.  The Official Secrets Act was a powerful instrument for almost a half-century after World War II, and it must have been even stronger back then. Obviously, this site had been carefully chosen for its isolation (among several other reasons) as a training facility for international espionage agents. Lethal weapons were tested there. Mock-Nazi buildings were constructed for simulated invasions. Personnel from the United States could surreptitiously enter the camp from the lakeshore without attracting much attention. Also, Thornton Road leads directly to the western boundary of the Oshawa Airport slightly over six miles to the north through farmland with only the small community of homes at Thornton's Corners, much less developed than the streets closer to Oshawa; in fact, the city's bus routes did not extend west of Gibbon Street for many years after the war. The base was even closer to rail lines which could bring supplies and equipment without attracting attention. During its use as a secret base, there were two tall communication towers not far from where the monument now stood. Wartime Oshawa was only a medium-sized city, but adequate enough to support a hidden camp. Even today the site of the spy-school is austere, uninviting and mysterious. Its existence remained a carefully guarded top secret for many years after the war.

The Official Secrets Act was a powerful instrument for almost a half-century after World War II, and it must have been even stronger back then. Obviously, this site had been carefully chosen for its isolation (among several other reasons) as a training facility for international espionage agents. Lethal weapons were tested there. Mock-Nazi buildings were constructed for simulated invasions. Personnel from the United States could surreptitiously enter the camp from the lakeshore without attracting much attention. Also, Thornton Road leads directly to the western boundary of the Oshawa Airport slightly over six miles to the north through farmland with only the small community of homes at Thornton's Corners, much less developed than the streets closer to Oshawa; in fact, the city's bus routes did not extend west of Gibbon Street for many years after the war. The base was even closer to rail lines which could bring supplies and equipment without attracting attention. During its use as a secret base, there were two tall communication towers not far from where the monument now stood. Wartime Oshawa was only a medium-sized city, but adequate enough to support a hidden camp. Even today the site of the spy-school is austere, uninviting and mysterious. Its existence remained a carefully guarded top secret for many years after the war.  One of the camp's trainees described being met at the Oshawa Grey Coach Lines bus terminal, driven west on King Street by truck to the outskirts, turning south, making several stops with the truck's headlights blinking signals, crossing two sets of railroad tracks (CNR and CPR), making a wide turn to the right near the lakeshore, and arriving at a well-guarded compound surrounded by electric fences.

One of the camp's trainees described being met at the Oshawa Grey Coach Lines bus terminal, driven west on King Street by truck to the outskirts, turning south, making several stops with the truck's headlights blinking signals, crossing two sets of railroad tracks (CNR and CPR), making a wide turn to the right near the lakeshore, and arriving at a well-guarded compound surrounded by electric fences.

I was lucky that it was a Sunday; the only parking was at a lot beside an auto-workers' union facility. Proceeding from there on foot, I followed an asphalt pathway for some distance before I discovered that it would not lead to the curved wall, which now appeared to be the monument about which I had read. I noticed a river and some mounds of earth downhill to the west before I climbed the grassy slope towards the monument. The top plaque was inscribed, as follows:

I was lucky that it was a Sunday; the only parking was at a lot beside an auto-workers' union facility. Proceeding from there on foot, I followed an asphalt pathway for some distance before I discovered that it would not lead to the curved wall, which now appeared to be the monument about which I had read. I noticed a river and some mounds of earth downhill to the west before I climbed the grassy slope towards the monument. The top plaque was inscribed, as follows:

CAMP X |